On his first night after leaving prison, Matthew Lincoln had an anxiety attack.

Suddenly, he was living in Albuquerque, which, to Lincoln, was a big city. Lincoln grew up a couple of hours away in Navajo Nation near Gallup. Separated from family and friends and living in a strange place, he felt afraid.

“I was not used to being free,” he says.

Fortunately, Lincoln had support from the Community Peer Education Program (CPEP), which gave him access to critical resources such as clothing and—even more importantly—helped him develop the confidence he needed to secure employment and survive on his own.

A Path Forward

CPEP, a program of Project ECHO, launched in 2020 to support people transitioning out of incarceration. It builds on the success of the New Mexico Peer Education Program, which trains people in prison to be health educators, equipping them to teach preventive health and hygiene to their peers. Today, many former peer educators work for CPEP in their communities, guiding people on probation or parole through challenges such as housing, employment, and access to health care.

In less than five years, CPEP has helped more than 3,800 people start new lives. Preliminary results from a two-year evaluation show that the longer participants stay connected with CPEP, the more successful they are at getting the resources they need to succeed. In addition, the evaluation finds that CPEP takes on a high percentage of former inmates who have mental health issues and are at high risk, and that CPEP specifically helps connect people with housing and employment, which are major challenges for people under community supervision.

Where Lincoln grew up, rates of alcoholism, opioid addiction, and suicide are high and often span generations. Lincoln says that he struggles with alcohol use disorder. Over the years, he racked up a series of DWI offenses. Finally, he was sentenced to a year in prison. With good behavior, he served only five months and was released in June on probation and parole.

However, there weren’t any community supervision spots available for him near Gallup. Albuquerque was his only choice. His family and friends back home couldn’t afford to make the two-and-a-half-hour car trip for visits, which left Lincoln feeling isolated and anxious.

“Re-entry was a big step,” he says. “I had to see if my wings could fly.”

Hope and Self-Confidence: Keys to Success

CPEP has been his bedrock. Sarah, his community peer educator, is in touch with Lincoln every week, connecting him to needed resources and encouraging him on his journey of re-entry into the community and recovery from alcoholism. She also shares her own experiences, as someone who’s been in his shoes.

In addition, Lincoln participates in weekly CPEP Zoom calls, where he and other people in re-entry listen to presentations on topics related to re-entry and talk about their challenges. He also attends online Alcoholics Anonymous meetings.

All this has given him hope. He sees the world—and himself—in a new, positive light. He believes in his ability to succeed.

“CPEP has helped me move forward in life and find a better understanding of myself,” he says.

Lincoln says that going to prison and participating in CPEP has made him a better man. He’s stayed sober and is living in his own apartment, making good money as a general laborer.

He hopes that eventually he can get his commercial driver’s license back. He’s also interested in becoming a CPE, like Sarah, and helping other people transitioning from incarceration.

“I’m grateful that a higher power has brought me here to grow up some more,” he says.

For more information about the Community Peer Education Program, email the program team.

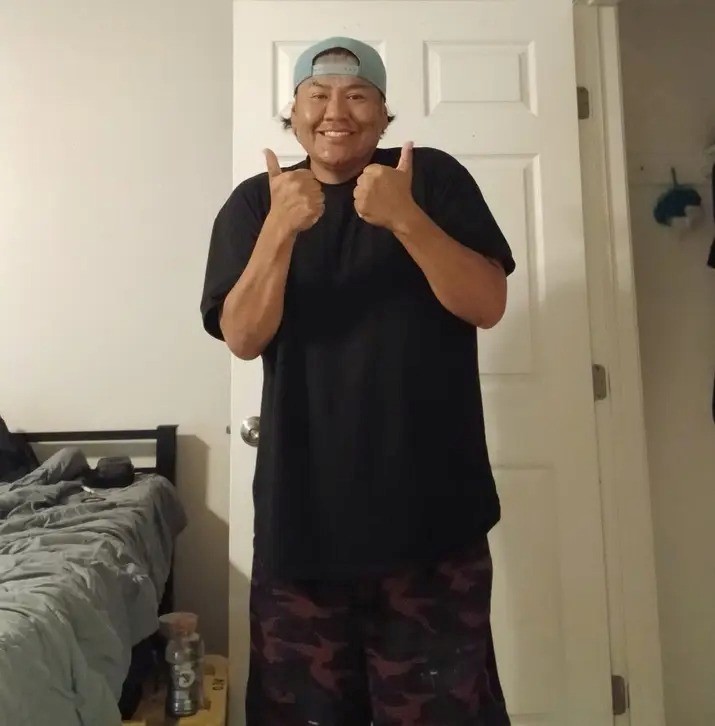

Featured Image: A self-portrait of Matthew Lincoln, taken the day he got out of prison. Photo Credit: June 2025.