“The bottom line is: this was very, very scary,” says Irene Atuhairwe Duhaga, country director for Seed Global Health, a nonprofit partnering with Project ECHO. Uganda had experienced Ebola outbreaks before, but they happened in the countryside. In 2022, the outbreak spread to Kampala, one of the country’s biggest cities.

“It’s a congested city,” Duhaga adds, “[and Ebola] is a deadline virus that spreads by contact. The potential for it to blow up was very high.”

The idea to use the ECHO Model came up after Duhaga and her team visited one of the emergency centers at the beginning of the outbreak, where they saw how chaotic things could get. “What if people started to travel to Kampala instead of staying at their local emergency management center?,” says Duhaga. “What if health workers were spreading the virus because they weren’t protected? This was our solution that could target all health workers across the country.”

Fortunately, resources were already in place to train health workers to stop the disease.

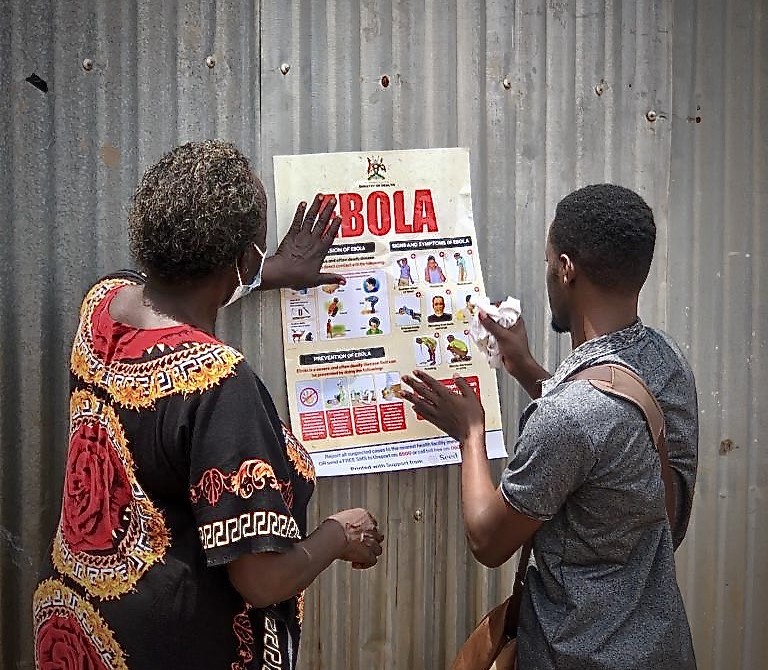

Two community health workers hang a poster designed to combat misinformation on the Sudanese strain of the Ebola virus. Photo Credit: Seed Global Health

Leveraging the Network

Seed Global Health and Jhpiego, two nonprofits with longstanding roots in Uganda, had been using the ECHO Model since 2016 for infectious disease control and HIV treatment.

“We already had the ECHO network from working with HIV ECHO Programs and Emergency Medicine ECHO Programs,” says Isaak Mukama, technology coordinator for Jhpiego. “For Ebola, we were able to work with the CDC to get ready for an emergency response ECHO.”

“It is not intuitive to treat Ebola or understand it,” says Duhaga. “Ebola is [often] thought of as untreatable. But you can treat the symptoms to help people survive the viral course.”

Ebola is only briefly taught in medical training; it’s important that health workers know how it’s spread—through body fluids including sweat, blood and breast milk—and how to protect themselves while treating.

This combination of local partnerships and a trained understanding of the ECHO Model made a world of difference. An Ebola emergency response ECHO program was established within days.

“We covered everything from laboratory tests, to collection case management, to referrals,” Mukama explains. “Usually for our programs, we have an ECHO session once every two weeks, but because of the nature of the emergency, we were meeting every day.”

Health care workers learn how to correctly put on personal protective equipment. Photo Credit: Seed Global Health

Nearly 850 participants in the emergency response ECHO learned best practices from global infectious disease specialists, including World Health Organization physicians, Ugandan researchers and experts in emergency medicine. The outbreak was declared over within four months, with 164 confirmed cases – 34% were fatal.

By applying the ECHO Model, a crisis was mitigated. “This was the platform that gave the right information to health care workers,” Mukama says. “Because the frontline team had the information they needed, we contained the outbreak.”

Featured Image Credit: A training for health care workers during the Ebola outbreak. Photo Credit: Seed Global Health.

For more information on ECHO’s work in Africa, email Dr. Caroline Kisia, director of ECHO Africa.