The ECHO Model is able to expand specialist care beyond major medical centers – a key tool in a country that has just four specialized physicians for every 10,000 people.

“Before ECHO, we did not at all have a virtual platform for capacity building. With our specialist shortage, we still send doctors from cancer specialist hospitals in cities to various rural states,” says Dr. Rosmawati Mohamed, clinical specialist for two ECHO programs focused on liver cancer and the Academy of Medicine of Malaysia’s chief chairperson. She was an early proponent of what the ECHO Model can do for physician training.

The first ECHO program in Malaysia was focused on liver cancer; today, there are programs for breast cancer, gynecological cancers, head and neck cancer, and palliative care. And, the government of Malaysia recently turned to ECHO to support cancer patient navigation – or a person who supports cancer patients in getting access to quality treatment.

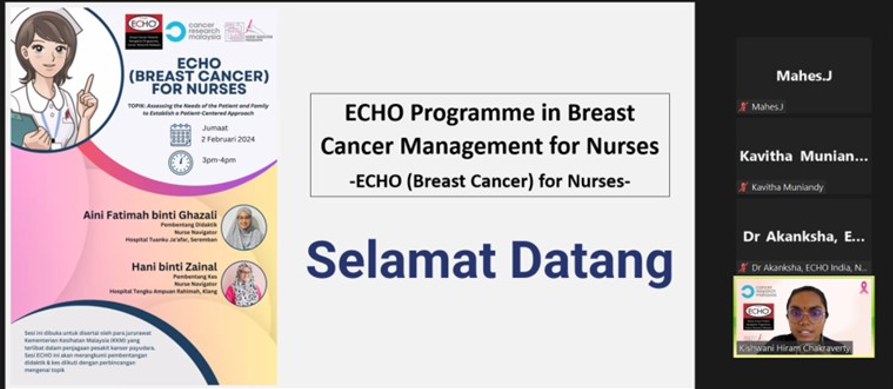

A nurse “navigator,” who supports patients navigate their cancer journey, presents a training for other nurses as part of an ECHO session. Credit: Cancer Research Malaysia, Cancer Patient Navigation ECHO Programs, October 2023.

Supporting a National Strategy

Project ECHO’s first partners in Malaysia were the University of Malay and the Malaysian Hospice and Palliative Care Council. Using the ECHO Model, they trained and mentored health care workers and patient navigation specialists across the country through virtual, case-based learning.

Following in their footsteps, the Academy of Medicine of Malaysia—the country’s central professional organization for doctors—recently signed an agreement with ECHO in a ceremony attended by the Minister of Health, YB Datuk Seri Dr. Dzulkefly Ahmad.

Project ECHO’s partners in Malaysia directly support the government’s national cancer strategic plan; most recently, they’ve focused on greater physician education for liver and breast cancer—two high-mortality cancers—as well as “navigator” support for cancer patients.

ECHO is a first step in reaching rural areas. In western Malaysia, even primary care is difficult to access, and patients often do not know how to access specialized care for a cancer diagnosis.

“It is difficult to multiply doctors immediately, but it is easier to build the capacity of our current doctors so that they can provide diagnoses and treatment in their own geography,” says Dr. Mohamed.

Bridging the Gap in Care

Dr. Woon Fang NG, chairperson for the Malaysian Hospice and Palliative Care Council and a palliative medicine specialist, believes ECHO can also create greater equity, and understanding, for her patients.

While palliative and hospice care can be part of cancer treatment, Dr. Woon believes more patients across health conditions need access to care for what she calls “health-related suffering.”

“We want to promote a compassionate community,” says Dr. Woon. “In the past, before we started Project ECHO for palliative care, the nurses involved in outpatient hospice care used to work in isolation from their colleagues, including our palliative care physicians running the in-patient service in hospitals, partially because people thought hospital-based care meant outpatient care had failed.”

“What we see is ECHO bridges this discontinuity. Instead of judging each other for differences between in-patient and outpatient, we share evidence of best practices. We share experiences. Everybody comes together with the ECHO Model,” Dr. Woon adds.

To learn more about Project ECHO in Malaysia, or throughout the Asia-Pacific, email us.

Featured Image: Dr. Kishwani Hiram Chakravarty presents to a group of nurses in the oncology department at a state referral hospital, as part of the cancer patient navigation programs. Credit: Cancer Research Malaysia, October 2023.